Discharge Debt | Home

Education Level | Are You Sovereign Or Not | NESARA | Do It Yourself Credit Card, Secured & Unsecured Debt Elimination, Redemption Program & More | Freedom | Are You Really Free | Debt Elimination Facts | Modern Money Mechanics | Clarification of The 14Th Amendment | Bankers Manifesto | Famous Quotes | Who Runs The US | Audio For All Credit Facts | Montgomery vs Daly | Justice Mahony's Memorandum | To help you to understand all about Unsecured Debt | The Truth & All The Facts Will Set You Free | Citizenship | The Law | Issues of Federal Jurisdiction | Constitutions | The Great Banking Deception | Memorandum Of Law | Bank Loans The Rest Of The Story | Did You Really Get A Loan | U.S. Bankruptcy | A WORD OF CAUTION TO THE MEEK | Dear Patriot | Who You Are | White Paper on State Citizenship | Two Faces Of Debt | Discharge Debt & New Energy Books Web Additions | Book Store

Modern Money Mechanics

MODERN MONEY MECHANICS

A Workbook on Bank Reserves and Deposit Expansion

This complete booklet is available in printed form free of charge from:

Public Information Center

Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago

P. O. Box 834

Chicago, IL 60690-0834

telephone: 312 322 5111

|

Introduction

The purpose of this booklet is to describe the basic process of money creation in a "fractional reserve" banking system. The approach taken illustrates the changes in bank balance sheets that occur when deposits in banks change as a result of monetary action by the Federal Reserve System - the central bank of the United States. The relationships shown are based on simplifying assumptions. For the sake of simplicity, the relationships are shown as if they were mechanical, but they are not, as is described later in the booklet. Thus, they should not be interpreted to imply a close and pred ictable relationship between a specific central bank transaction and the quantity of money.

The introductory pages contain a brief general description of the characteristics of money and how the U.S. money system works. The illustrations in the following two sections describe two processes: first, how bank deposits expand or contract in response to changes in the amount of reserves supplied by the central bank; and second, how those reserves are affected by both Federal Reserve actions and other factors. A final section deals with some of the elements that modify, at least in the short run, the simple mechanical relationship between bank reserves and deposit money.

Money is such a routine part of everyday living that its existence and acceptance ordinarily are taken for granted. A user may sense that money must come into being either automatically as a result of economic activity or as an outgrowth of some government operation. But just how this happens all too often remains a mystery.

What is Money?

If money is viewed simply as a tool used to facilitate transactions, only those media that are readily accepted in exchange for goods, services, and other assets need to be considered. Many things - from stones to baseball cards - have served this monetary function through the ages. Today, in the United States, money used in transactions is mainly of three kinds - currency (paper money and coins in the pockets and purses of the public); demand deposits (non-interest bearing checking accounts in banks); and other checkable deposits, such as negotiable order of withdrawal (NOW) accounts, at all depository institutions, including commercial and savings banks, savings and loan associations, and credit unions. Travelers checks also are included in the definition of transactions money. Since $1 in currency and $1 in checkable deposits are freely convertible into each other and both can be used directly for expenditures, they are money in equal degree. However, only the cash and balances held by the nonbank public are counted in the money supply. Deposits of the U.S. Treasury, depository institutions, foreign banks and official institutions, as well as vault cash in depository institutions are excluded.

This transactions concept of money is the one designated as M1 in the Federal Reserve's money stock statistics. Broader concepts of money (M2 and M3) include M1 as well as certain other financial assets (such as savings and time deposits at depository institutions and shares in money market mutual funds) which are relatively liquid but believed to represent principally investments to their holders rather than media of exchange. While funds can be shifted fairly easily between transaction balances and these other liquid assets, the money-creation process takes place principally through transaction accounts. In the remainder of this booklet, "money" means M1.

The distribution between the currency and deposit components of money depends largely on the preferences of the public. When a depositor cashes a check or makes a cash withdrawal through an automatic teller machine, he or she red uces the amount of deposits and increases the amount of currency held by the public. Conversely, when people have more currency than is needed, some is returned to banks in exchange for deposits.

While currency is used for a great variety of small transactions, most of the dollar amount of money payments in our economy are made by check or by electronic transfer between deposit accounts. Moreover, currency is a relatively small part of the money stock. About 69 percent, or $623 billion, of the $898 billion total stock in December 1991, was in the form of transaction deposits, of which $290 billion were demand and $333 billion were other checkable deposits.

What Makes Money Valuable?

In the United States neither paper currency nor deposits have value as commodities. Intrinsically, a dollar bill is just a piece of paper, deposits merely book entries. Coins do have some intrinsic value as metal, but generally far less than their face value.

What, then, makes these instruments - checks, paper money, and coins - acceptable at face value in payment of all debts and for other monetary uses? Mainly, it is the confidence people have that they will be able to exchange such money for other financial assets and for real goods and services whenever they choose to do so.

Money, like anything else, derives its value from its scarcity in relation to its usefulness. Commodities or services are more or less valuable because there are more or less of them relative to the amounts people want. Money's usefulness is its unique ability to command other goods and services and to permit a holder to be constantly ready to do so. How much money is demanded depends on several factors, such as the total volume of transactions in the economy at any given time, the payments habits of the society, the amount of money that individuals and businesses want to keep on hand to take care of unexpected transactions, and the forgone earnings of holding financial assets in the form of money rather than some other asset.

Control of the quantity of money is essential if its value is to be kept stable. Money's real value can be measured only in terms of what it will buy. Therefore, its value varies inversely with the general level of prices. Assuming a constant rate of use, if the volume of money grows more rapidly than the rate at which the output of real goods and services increases, prices will rise. This will happen because there will be more money than there will be goods and services to spend it on at prevailing prices. But if, on the other hand, growth in the supply of money does not keep pace with the economy's current production, then prices will fall, the nations's labor force, factories, and other production facilities will not be fully employed, or both.

Just how large the stock of money needs to be in order to handle the transactions of the economy without exerting undue influence on the price level depends on how intensively money is being used. Every transaction deposit balance and every dollar bill is part of someBODY background="modbkgnd.jpg"'s spendable funds at any given ti me, ready to move to other owners as transactions take place. Some holders spend money quickly after they get it, making these funds available for other uses. Others, however, hold money for longer periods. Obviously, when some money remains idle, a larger total is needed to accomplish any given volume of transactions.

Who Creates Money?

Changes in the quantity of money may originate with actions of the Federal Reserve System (the central bank), depository institutions (principally commercial banks), or the public. The major control, however, rests with the central bank.

The actual process of money creation takes place primarily in banks. As noted earlier, checkable liabilities of banks are money. These liabilities are customers' accounts. They increase when customers deposit currency and checks and when the proceeds of loans made by the banks are credited to borrowers' accounts.

In the absence of legal reserve requirements, banks can build up deposits by increasing loans and investments so long as they keep enough currency on hand to redeem whatever amounts the holders of deposits want to convert into currency. This unique attribute of the banking business was discovered many centuries ago.

It started with goldsmiths. As early bankers, they initially provided safekeeping services, making a profit from vault storage fees for gold and coins deposited with them. People would redeem their "deposit receipts" whenever they needed gold or coins to purchase something, and physically take the gold or coins to the seller who, in turn, would deposit them for safekeeping, often with the same banker. Everyone soon found that it was a lot easier simply to use the deposit receipts directly as a means of payment. These receipts, which became known as notes, were acceptable as money since whoever held them could go to the banker and exchange them for metallic money.

Then, bankers discovered that they could make loans merely by giving their promises to pay, or bank notes, to borrowers. In this way, banks began to create money. More notes could be issued than the gold and coin on hand because only a portion of the notes outstanding would be presented for payment at any one time. Enough metallic money had to be kept on hand, of course, to redeem whatever volume of notes was presented for payment.

Transaction deposits are the modern counterpart of bank notes. It was a small step from printing notes to making book entries crediting deposits of borrowers, which the borrowers in turn could "spend" by writing checks, thereby "printing" their own money.

What Limits the Amount of Money Banks Can Create?

If deposit money can be created so easily, what is to prevent banks from making too much - more than sufficient to keep the nation's productive resources fully employed without price inflation? Like its predecessor, the modern bank must keep available, to make payment on demand, a considerable amount of currency and funds on deposit with the central bank. The bank must be prepared to convert deposit money into currency for those depositors who request currency. It must make remittance on checks written by depositors and presented for payment by other banks (settle adverse clearings). Finally, it must maintain legally required reserves, in the form of vault cash and/or balances at its Federal Reserve Bank, equal to a prescribed percentage of its deposits.

The public's demand for currency varies greatly, but generally follows a seasonal pattern that is quite predictable. The effects on bank funds of these variations in the amount of currency held by the public usually are offset by the central bank, which replaces the reserves absorbed by currency withdrawals from banks. (Just how this is done will be explained later.) For all banks taken together, there is no net drain of funds through clearings. A check drawn on one bank normally will be deposited to the credit of another account, if not in the same bank, then in some other bank.

These operating needs influence the minimum amount of reserves an individual bank will hold voluntarily. However, as long as this minimum amount is less than what is legally required, operating needs are of relatively minor importance as a restraint on aggregate deposit expansion in the banking system. Such expansion cannot continue beyond the point where the amount of reserves that all banks have is just sufficient to satisfy legal requirements under our "fractional reserve" system. For example, if reserves of 20 percent were required, deposits could expand only until they were five times as large as reserves. Reserves of $10 million could support deposits of $50 million. The lower the percentage requirement, the greater the deposit expansion that can be supported by each additional reserve dollar. Thus, the legal reserve ratio together with the dollar amount of bank reserves are the factors that set the upper limit to money creation.

What Are Bank Reserves?

Currency held in bank vaults may be counted as legal reserves as well as deposits (reserve balances) at the Federal Reserve Banks. Both are equally acceptable in satisfaction of reserve requirements. A bank can always obtain reserve balances by sending currency to its Reserve Bank and can obtain currency by drawing on its reserve balance. Because either can be used to support a much larger volume of deposit liabilities of banks, currency in circulation and reserve balances together are often referred to as "high-powered money" or the "monetary base." Reserve balances and vault cash in banks, however, are not counted as part of the money stock held by the public.

For individual banks, reserve accounts also serve as working balances. Banks may increase the balances in their reserve accounts by depositing checks and proceeds from electronic funds transfers as well as currency. Or they may draw down these balances by writing checks on them or by authorizing a debit to them in payment for currency, customers' checks, or other funds transfers.

Although reserve accounts are used as working balances, each bank must maintain, on the average for the relevant reserve maintenance period, reser ve balances at their Reserve Bank and vault cash which together are equal to its required reserves, as determined by the amount of its deposits in the reserve computation period.

Where Do Bank Reserves Come From?

Increases or decreases in bank reserves can result from a number of factors discussed later in this booklet. From the standpoint of money creation, however, the essential point is that the reserves of banks are, for the most part, liabilities of the Federal Reserve Banks, and net changes in them are largely determined by actions of the Federal Reserve System. Thus, the Federal Reserve, through its ability to vary both the total volume of reserves and the required ratio of reserves to deposit liabilities, influences banks' decisions with respect to their assets and deposits. One of the major responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System is to provide the total amount of reserves consistent with the monetary needs of the economy at reasonably stable prices. Such actions take into consideration, of course, any changes in the pace at which money is being used and changes in the public's demand for cash balances.

The reader should be mindful that deposits and reserves tend to expand simultaneously and that the Federal Reserve's control often is exerted through the market place as individual banks find it either cheaper or more expensive to obtain their required reserves, depending on the willingness of the Fed to support the current rate of credit and deposit expansion.

While an individual bank can obtain reserves by bidding them away from other banks, this cannot be done by the banking system as a whole. Except for reserves borrowed temporarily from the Federal Reserve's discount window, as is shown later, the supply of reserves in the banking system is controlled by the Federal Reserve.

Moreover, a given increase in bank reserves is not necessarily accompanied by an expansion in money equal to the theoretical potential based on the required ratio of reserves to deposits. What happens to the quantity of money will vary, depending upon the reactions of the banks and the public. A number of slippages may occur. What amount of reserves will be drained into the public's currency holdings? To what extent will the increase in total reserves remain unused as excess reserves? How much will be absorbed by deposits or other liabilities not defined as money but against which banks might also have to hold reserves? How sensitive are the banks to policy actions of the central bank? The significance of these questions will be discussed later in this booklet. The answers indicate why changes in the money supply may be different than expected or may respond to policy action only after considerable time has elapsed.

In the succeeding pages, the effects of various transactions on the quantity of money are described and illustrated. The basic working tool is the "T" account, which provides a simple means of tracing, step by step, the effects of these transactions on both the asset and liability sides of bank balance sheets. Changes in asset items are entered on the left half of the "T" and changes in liabilities on the right half. For any one transaction, of course, there must be at least two entries in order to maintain the equality of assets and liabilities.

1In order to describe the money-creation process as simply as possible, the term "bank" used in this booklet should be understood to encompass all depository institutions. Since the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, all depository institutions have been permitted to offer interest bearing transaction accounts to certain customers. Transaction accounts (interest bearing as well as demand deposits on which payment of interest is still legally prohibited) at all depository institutions are subject to the reserve requirements set by the Federal Reserve. Thus all such institutions, not just commercial banks, have the potential for creating money.

2Part of an individual bank's reserve account may represent its reserve balance used to meet its reserve requirements while another part may be its required clearing balance on which earnings credits are generated to pay for Federal Reserve Bank services.

Bank Deposits - How They Expand or Contract

Let us assume that expansion in the money stock is desired by the Federal Reserve to achieve its policy objectives. One way the central bank can initiate such an expansion is through purchases of securities in the open market. Payment for the securities adds to bank reserves. Such purchases (and sales) are called "open market operations."

How do open market purchases add to bank reserves and deposits? Suppose the Federal Reserve System, through its trading desk at t he Federal Reserve Bank of New York, buys $10,000 of Treasury bills from a dealer in U. S. government securities. In today's world of computerized financial transactions, the Federal Reserve Bank pays for the securities with an "telectronic" check drawn on itself.Via its "Fedwire" transfer network, the Federal Reserve notifies the dealer's designated bank (Bank A) that payment for the securities should be credited to (deposited in) the dealer's account at Bank A. At the same time, Bank A's reserve account at the Federal Reserve is credited for the amount of the securities purchase. The Federal Reserve System has added $10,000 of securities to its assets, which it has paid for, in effect, by creating a liability on itself in the form of bank reserve balances. These reserves on Bank A's books are matched by $10,000 of the dealer's deposits that did not exist before. See illustration 1.

How the Multiple Expansion Process Works

If the process ended here, there would be no "multiple" expansion, i.e., deposits and bank reserves would have changed by the same amount. However, banks are required to maintain reserves equal to only a fraction of their deposits. Reserves in excess of this amount may be used to increase earning assets - loans and investments. Unused or excess reserves earn no interest. Under current regulations, the reserve requirement against most transaction accounts is 10 percent. Assuming, for simplicity, a uniform 10 percent reserve requirement against all transaction deposits, and further assuming that all banks attempt to remain fully invested, we can now trace the process of expansion in deposits which can take place on the basis of the additional reserves provided by the Federal Reserve System's purchase of U. S. government securities.

The expansion process may or may not begin with Bank A, depending on what the dealer does with the money received from the sale of securities. If the dealer immediately writes checks for $10,000 and all of them are deposited in other banks, Bank A loses both deposits and reserves and shows no net change as a result of the System's open market purchase. However, other banks have received them. Most likely, a part of the initial deposit will remain with Bank A, and a part will be shifted to other banks as the dealer's checks clear.

It does not really matter where this money is at any given time. The important fact is that these deposits do not disappear. They are in some deposit accounts at all times. All banks together have $10,000 of deposits and reserves that they did not have before. However, they are not required to keep $10,000 of reserves against the $10,000 of deposits. All they need to retain, under a 10 percent reserve requirement, is $1000. The remaining $9,000 is "excess reserves." This amount can be loaned or invested. See illustration 2.

If business is active, the banks with excess reserves probably will have opportunities to loan the $9,000. Of course, they do not really pay out loans from the money they receive as deposits. If they did this, no additional money would be created. What they do when they make loans is to accept promissory notes in exchange for credits to the borrowers' transaction accounts. Loans (assets) and deposits (liabilities) both rise by $9,000. Reserves are unchanged by the loan transactions. But the deposit credits constitute new additions to the total deposits of the banking system. See illustration 3.

3Dollar amounts used in the various illustrations do not necessarily bear any resemblance to actual transactions. For example, open market operations typically are conducted with many dealers and in amounts totaling several billion dollars.

4Indeed, many transactions today are accomplished through an electronic transfer of funds between accounts rather than through issuance of a paper check. Apart from the time of posting, the accounting entries are the same whether a transfer is made with a paper check or electronically. The term "check," therefore, is used for both types of transfers.

5For each bank, the reserve requirement is 3 percent on a specified base amount of transaction accounts and 10 percent on the amount above this base. Initially, the Monetary Control Act set this base amount - called the "low reserve tranche" - at $25 million, and provided for it to change annually in line with the growth in transaction deposits nationally. The low reserve tranche was $41.1 million in 1991 and $42.2 million in 1992. The Garn-St. Germain Act of 1982 further modified these requirements by exempting the first $2 million of reservable liabilities from reserve requirements. Like the low reserve tranche, the exempt level is adjusted each year to reflect growth in reservable liabilities. The exempt level was $3.4 million in 1991 and $3.6 million in 1992.

Deposit Expansion

1. When the Federal Reserve Bank purchases government securities, bank reserves increase. This happens because the seller of the securities receives payment through a credit to a designated deposit account at a bank (Bank A) which the Federal Reserve effects by crediting the reserve account of Bank A.

FR BANK

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

US govt

securities.. +10,000

|

Reserve acct.

Bank A.. +10,000

|

Reserves with

FR Banks.. +10,000

|

Customer

deposit.. +10,000

|

The customer deposit at Bank A likely will be transferred, in part, to other banks and quickly loses its identity amid the huge interbank flow of deposits.

2.As a result, all banks taken together

now have "excess" reserves on which

deposit expansion can take place.

|

Total reserves gained from new deposits.......10,000

less: required against new deposits (at 10%)... 1,000

equals: Excess reserves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9,000

|

Expansion - Stage 1

3.Expansion takes place only if the banks that hold these excess reserves (Stage 1 banks) increase their loans or investments. Loans are made by crediting the borrower's account, i.e., by creating additional deposit money.

STAGE 1 BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Loans....... +9,000

|

Borrower deposits.... +9,000

|

This is the beginning of the deposit expansion process. In the first stage of the process, total loans and deposits of the banks rise by an amount equal to the excess reserves existing before any loans were made (90 percent of the initial deposit increase). At the end of Stage 1, deposits have risen a total of $19,000 (the initial $10,000 provided by the Federal Reserve's action plus the $9,000 in deposits created by Stage 1 banks). See illustration 4. However, only $900 (10 percent of $9000) of excess reserves have been absorbed by the additional deposit growth at Stage 1 banks. See illustration 5.

The lending banks, however, do not expect to retain the deposits they create through their loan operations. Borrowers write checks that probably will be deposited in other banks. As these checks move through the collection process, the Federal Reserve Banks debit the reserve accounts of the paying banks (Stage 1 banks) and credit those of the receiving banks. See illustration 6.

Whether Stage 1 banks actually do lose the deposits to other banks or whether any or all of the borrowers' checks are redeposited in these same banks makes no difference in the expansion process. If the lending banks expect to lose these deposits - and an equal amount of reserves - as the borrowers' checks are paid, they will not lend more than their excess reserves. Like the original $10,000 deposit, the loan-credited deposits may be transferred to other banks, but they remain somewhere in the banking system. Whichever banks receive them also acquire equal amounts of reserves, of which all but 10 percent will be "excess."

Assuming that the banks holding the $9,000 of deposits created in Stage 1 in turn make loans equal to their excess reserves, then loans and deposits will rise by a further $8,100 in the second stage of expansion. This process can continue until deposits have risen to the point where all the reserves provided by the initial purchase of government securities by the Federal Reserve System are just sufficient to satisfy reserve requirements against the newly created deposits.(See pages 10 and 11.)

The individual bank, of course, is not concerned as to the stages of expansion in which it may be participating. Inflows and outflows of deposits occur continuously. Any deposit received is new money, regardless of its ultimate source. But if bank policy is to make loans and investments equal to whatever reserves are in excess of legal requirements, the expansion process will be carried on.

How Much Can Deposits Expand in the Banking System?

The total amount of expansion that can take place is illustrated on page 11. Carried through to theoretical limits, the initial $10,000 of reserves distributed within the banking system gives rise to an expansion of $90,000 in bank credit (loans and investments) and supports a total of $100,000 in new deposits under a 10 percent reserve requirement. The deposit expansion factor for a given amount of new reserves is thus the reciprocal of the required reserve percentage (1/.10 = 10). Loan expansion will be less by the amount of the initial injection. The multiple expansion is possible because the banks as a group are like one large bank in which checks drawn against borrowers' deposits result in credits to accounts of other depositors, with no net change in the total reserves.

Expansion through Bank Investments

Deposit expansion can proceed from investments as well as loans. Suppose that the demand for loans at some Stage 1 banks is slack. These banks would then probably purchase securities. If the sellers of the securities were customers, the banks would make payment by crediting the customers' transaction accounts, deposit liabilities would rise just as if loans had been made. More likely, these banks would purchase the securities through dealers, paying for them with checks on themselves or on their reserve accounts. These checks would be deposited in the sellers' banks. In either case, the net effects on the banking system are identical with those resulting from loan operations.

4 As a result of the process so far, total assets and total liabilities of all banks together have risen 19,000. back

ALL BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F. R. Banks...+10,000

Loans . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . + 9,000

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . +19,000

|

Deposits: Initial. . . .+10,000

Stage 1 . . . . . . . . . + 9,000

Total . . . . . . . . . . .+19,000

|

5Excess reserves have been reduced by the amount required against the deposits created by the loans made in Stage 1.

Total reserves gained from initial deposits. . . . 10,000

less: Required against initial deposits . . . . . . . . -1,000

less: Required against Stage 1 requirements . . . . -900

equals: Excess reserves. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8,100

|

Why do these banks stop increasing their loans

and deposits when they still have excess reserves?

6 ...because borrowers write checks on their accounts at the lending banks. As these checks are deposited in the payees' banks and cleared, the deposits created by Stage 1 loans and an equal amount of reserves may be transferred to other banks.

STAGE 1 BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F. R. Banks . -9000

(matched under FR bank

liabilities)

|

Borrower deposits . . . -9,000

(shown as additions to

other bank deposits)

|

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserve accounts: Stage 1 banks . -9,000

Other banks. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . +9,000

|

OTHER BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F. R. Banks . +9,000

|

Deposits . . . . . . . . . +9,000

|

Deposit expansion has just begun!

Page 10.

7Expansion continues as the banks that have excess reserves increase their loans by that amount, crediting borrowers' deposit accounts in the process, thus creating still more money.

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

|

Loans . . . . . . . . + 8100

|

Borrower deposits . . . +8,100

|

8Now the banking system's assets and liabilities have risen by 27,100.

ALL BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F. R. Banks . +10,000

Loans: Stage 1 . . . . . . . . . . .+ 9,000

Stage 2 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . + 8,100

Total. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . +27,000

|

Deposits: Initial . . . . +10,000

Stage 1 . . . . . . . . . . . +9,000

Stage 2 . . . . . . . . . . . +8,100

Total . . . . . . . . . . . . +27,000

|

9 But there are still 7,290 of excess reserves in the banking system.

Total reserves gained from initial deposits . . . . . 10,000

less: Required against initial deposits . -1,000

less: Required against Stage 1 deposits . -900

less: Required against Stage 2 deposits . -810 . . . 2,710

equals: Excess reserves . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7,290 --> to Stage 3 banks

|

10 As borrowers make payments, these reserves will be further dispersed, and the process can continue through many more stages, in progressively smaller increments, until the entire 10,000 of reserves have been absorbed by deposit growth. As is apparent from the summary table on page 11, more than two-thirds of the deposit expansion potential is reached after the first ten stages.

It should be understood that the stages of expansion occur neither simultaneously nor in

the sequence described above. Some banks use their reserves incompletely or only after a

considerable time lag, while others expand assets on the basis of expected reserve growth.

The process is, in fact, continuous and may never reach its theoretical limits.

End page 10.

Page 11.

Thus through stage after stage of expansion,

"money" can grow to a total of 10 times the new

reserves supplied to the banking system....

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

[

|

Reserves

|

]

|

Total

|

(Required)

|

(Excess)

|

Loans and

Investments

|

Deposits

|

n

Reserves provided

|

10,000

|

1,000

|

9,000

|

-

|

10,000

|

Exp. Stage 1

|

10,000

|

1900

|

8,100

|

9,000

|

19,000

|

Stage2

|

10,000

|

2,710

|

7,290

|

17,100

|

27,100

|

Stage 3

|

10,000

|

3,439

|

6,561

|

24,390

|

34,390

|

Stage 4

|

10,000

|

4,095

|

5,905

|

30,951

|

40,951

|

Stage 5

|

10,000

|

4,686

|

5,314

|

36,856

|

46,856

|

Stage 6

|

10,000

|

5,217

|

4,783

|

42,170

|

52,170

|

Stage 7

|

10,000

|

5,695

|

4,305

|

46,953

|

56,953

|

Stage 8

|

10,000

|

6,126

|

3,874

|

51,258

|

61,258

|

Stage 9

|

10,000

|

6,513

|

3,487

|

55,132

|

65,132

|

Stage 10

|

10,000

|

6,862

|

3,138

|

58,619

|

68,619

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

Stage 20

|

10,000

|

8,906

|

1,094

|

79,058

|

89,058

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

...

|

Final Stage

|

10,000

|

10,000

|

0

|

90,000

|

100,000

|

...as the new deposits created by loans

at each stage are added to those created at all

earlier stages and those supplied by the initial

reserve-creating action.

End page 11.

Page 12.

How Open Market Sales Reduce bank Reserves and Deposits

Now suppose some reduction in the amount of money is desired. Normally this would reflect temporary or seasonal reductions in activity to be financed since, on a year-to-year basis, a growing economy needs at least some monetary expansion. Just as purchases of government securities by the Federal Reserve System can provide the basis for deposit expansion by adding to bank reserves, sales of securities by the Federal Reserve System reduce the money stock by absorbing bank reserves. The process is essentially the reverse of the expansion steps just described.

Suppose the Federal Reserve System sells $10,000 of Treasury bills to a U.S. government securities dealer and receives in payment an "electronic" check drawn on Bank A. As this payment is made, Bank A's reserve account at a Federal Reserve Bank is reduced by $10,000. As a result, the Federal Reserve System's holdings of securities and the reserve accounts of banks are both reduced $10,000. The $10,000 reduction in Bank A's depost liabilities constitutes a decline in the money stock. See illustration 11.

Contraction Also Is a Cumulative Process

While Bank A may have regained part of the initial reduction in deposits from other banks as a result of interbank deposit flows, all banks taken together have $10,000 less in both deposits and reserves than they had before the Federal Reserve's sales of securities. The amount of reserves freed by the decline in deposits, however, is only $1,000 (10 percent of $10,000). Unless the banks that lose the reserves and depos its had excess reserves, they are left with a reserve deficiency of $9,000. See illustration 12. Although they may borrow from the Federal Reserve Banks to cover this deficiency temporarily, sooner or later the banks will have to obtain the necessary reserves in some other way or reduce their needs for reserves.

One way for a bank to obtain the reserves it needs is by selling securities. But, as the buyers of the securities pay for them with funds in their deposit accounts in the same or other banks, the net result is a $9,000 decline in securities and deposits at all banks. See illustration 13. At the end of Stage 1 of the contraction process, deposits have been reduced by a total of $19,000 (the initial $10,000 resulting from the Federal Reserve's action plus the $9,000 in deposits extinguished by securities sales of Stage 1 banks). See illustration 14.

However, there is now a reserve deficiency of $8,100 at banks whose depositors drew down their accounts to purchase the securities from Stage 1 banks. As the new group of reserve-deficient banks, in turn, makes up this deficiency by selling securities or reducing loans, further deposit contraction takes place.

Thus, contraction proceeds through reductions in deposits and loans or investments in one stage after another until total deposits have been reduced to the point where the smaller volume of reserves is adequate to support them. The contraction multiple is the same as that which applies in the case of expansion. Under a 10 percent reserve requirement, a $10,000 reduction in reserves would ultimately entail reductions of $100,000 in deposits and $90,000 in loans and investments.

As in the case of deposit expansion, contraction of bank deposits may take place as a result of either sales of securities or reductions of loans. While some adjustments of both kinds undoubtedly would be made, the initial impact probably would be reflected in sales of government securities. Most types of outstanding loans cannot be called for payment prior to their due dates. But the bank may cease to make new loans or refuse to renew outstanding ones to replace those currently maturing. Thus, deposits built up by borrowers for the purpose of loan retirement would be extinguished as loans were repaid.

There is one important difference between the expansion and contraction processes. When the Federal Reserve System adds to bank reserves, expansion of credit and deposits may take place up to the limits permitted by the minimum reserve ratio that banks are required to maintain. But when the System acts to reduce the amount of bank reserves, contraction of credit and deposits must take place (except to the extent that existing excess reserve balances and/or surplus vault cash are utilized) to the point where the required ratio of reserves to deposits is restored. But the significance of this difference should not be overemphasized. Because exce ss reserve balances do not earn interest, there is a strong incentive to convert them into earning assets (loans and investments).

End of page 12.

Page 13.

Deposit Contraction

11When the Federal Reserve Bank sells government securities, bank reserves decline. This happens because the buyer of the securities makes payment through a debit to a designated deposit account at a bank (Bank A), with the transfer of funds being effected by a debit to Bank A's reserve account at the Federal Reserve Bank.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

U.S govt

securities....-10,000

|

Reserve Accts.

Bank A....-10,000

|

Reserves with

F.R. Banks....-10,000

|

Customer

deposts.....-10,000

|

This reduction in the customer deposit at Bank A may be spread

among a number of banks through interbank deposit flows.

12 The loss of reserves means that all banks taken together now have a reserve deficiency.

Total reserves lost from deposit withdrawal . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10,000

less: Reserves freed by deposit decline(10%). . . . . . . . . . . . . 1,000

equals: Deficiency in reserves against remaining deposits . . 9,000

|

Contraction - Stage 1

13 The banks with the reserve deficiencies (Stage 1 banks) can sell government securities to acquire reserves, but this causes a decline in the deposits and reserves of the buyers' banks.

STAGE 1 BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

U.S.government securities...-9,000

Reserves with F.R. Banks..+9,000

|

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

|

Reserve Accounts:

Stage 1 banks........+9,000

Other banks............-9,000

|

OTHER BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . . -9,000

|

Deposits . . . . -9,000

|

14 As a result of the process so far, assets and total deposits of all banks together have declined 19,000. Stage 1 contraction has freed 900 of reserves, but there is still a reserve deficiency of 8,100.

ALL BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . . -10,000

U.S. government securities . . -9,000

Total . . . . .-19,000

|

Deposits:

Initial . . . . . . . -10,000

Stage 1 . . . . . . -9,000

Total . . . . . . . -19,000

|

Further contraction must take place!

End of page 13.

Bank Reserves - How They Change

Money has been defined as the sum of transaction accounts in n depository institutions, and currency and travelers checks in the hands of the public. Currency is something almost everyone uses every day. Therefore, when most people think of money, they think of currency. Contrary to this popular impression, however, transaction deposits are the most significant part of the money stock. People keep enough currency on hand to effect small face-to-face transactions, but they write checks to cover most large expenditures. Most businesses probably hold even smaller amounts of currency in relation to their total transactions than do individuals.

Since the most important component of money is transaction deposits, and since these deposits must be supported by reserves, the central bank's influence over money hinges on its control over the total amount of reserves and the conditions under which banks can obtain them.

The preceding illustrations of the expansion and contraction processes have demonstrated how the central bank, by purchasing and selling government securities, can deliberately change aggregate bank reserves in order to affect deposits. But open market operations are only one of a number of kinds of transactions or developments that cause changes in reserves. Some changes originate from actions taken by the public, by the Treasury Department, by the banks, or by foreign and international institutions. Other changes arise from the service functions and operating needs of the Reserve Banks themselves.

The various factors that provide and absorb bank reserve balances, together with symbols indicating the effects of these developments, are listed on the opposite page. This tabulaton also indicates the nature of the balancing entries on the Federal Reserve's books. (To the extent that the impact is absorbed by changes in banks' vault cash, the Federal Reserve's books are unaffected.)

Independent Factors Versus Policy Action

It is apparent that bank reserves are affected in several ways that are independent of the control of the central bank. Most of these "independent" elements are changing more or less continually. Sometimes their effects may last only a day or two before being reversed automatically. This happens, for instance, when bad weather slows up the check collection process, giving rise to an automatic increase in Federal Reserve credit in the form of "float." Other influences, such as changes in the public's currency holdings, may persist for longer periods of time.

Still other variations in bank reserves result solely from the mechanics of institutional arrangements among the Treasury, the Federal Reserve Banks, and the depository institutions. The Treasury, for example, keeps part of its operating cash balance on deposit with banks. But virtually all disbursements are made from its balance in the Reserve Banks. As is shown later, any buildup in balances at the Reserve Banks prior to expenditure by the Treasury causes a dollar-for-dollar drain on bank reserves.

In contrast to these independent elements that affect reserves n are the policy actions taken by the Federal Reserve System. The way System open market purchases and sales of securities affect reserves has already been described. In addition, there are two other ways in which the System can affect bank reserves and potential deposit volume directly; first, through loans to depository institutions, and second, through changes in reserve requirement percentages. A change in the required reserve ratio, of course, does not alter the dollar volume of reserves directly but does change the amount of deposits that a given amount of reserves can support.

Any change in reserves, regardless of its origin, has the same potential to affect deposits. Therefore, in order to achieve the net reserve effects consistent with its monetary policy objectives, the Federal Reserve System continuously must take account of what the independent factors are doing to reserves and then, using its policy tools, offset or supplement them as the situation may require.

By far the largest number and amount of the System's gross open market transactions are undertaken to offset drains from or additions to bank reserves from non-Federal Reserve sources that might otherwise cause abrupt changes in credit availability. In addition, Federal Reserve purchases and/or sales of securities are made to provide the reserves needed to support the rate of money growth consistent with monetary policy objectives.

In this section of the booklet, several kinds of transactions that can have important week-to-week effects on bank reserves are traced in detail. Other factors that normally have only a small influence are described briefly on page 35.

Factors Changing Reserve Balances - Independent and Policy Actions

FEDERAL RESERVE BANKS

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserve

balances

|

Other

|

||

Public actions

|

|||

Increase in currency holdings...............

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in currency holdings.............

|

+

|

-

|

|

Treasury, bank, and foreign actions

|

|||

Increase in Treasury deposits in F.R. Banks......

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in Treasury deposits in F.R. Banks.....

|

+

|

-

|

|

Gold purchases (inflow) or increase in official valuation*..

|

+

|

-

|

|

Gold sales (outflows)*.......................

|

-

|

+

|

|

Increase in SDR certificates issued*....................

|

+

|

-

|

|

Decrease in SDR certificates issued*..................

|

-

|

+

|

|

Increase in Treasury currency outstanding*...................

|

+

|

-

|

|

Decrease in Treasury currency outstanding*...................

|

-

|

+

|

|

Increase in Treasury cash holdings*.........

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in Treasury cash holdings*.........

|

+

|

-

|

|

Increase in service-related balances/adjustments.....

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in service-related balances/adjustments.......

|

+

|

-

|

|

Increase in foreign and other deposits in F.R. Banks........

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in foreign and other deposits in F.R. Banks....

|

+

|

-

|

|

Federal Reserve actions

|

|||

Purchases of securities....................................

|

+

|

+

|

|

Sales of securities...................................

|

-

|

-

|

|

Loans to depository institutions...........

|

+

|

+

|

|

Repayment of loans to depository institutions.........

|

-

|

-

|

|

Increase in Federal Reserve float..................

|

+

|

+

|

|

Decrease in Federal Reserve float......................

|

-

|

-

|

|

Increase in assets denominated in foreign currency ......

|

+

|

+

|

|

Decrease in assets denominated in foreign currency ......

|

-

|

-

|

|

Increase in other assets**.....................................

|

+

|

+

|

|

Decrease in other assets**.....................................

|

-

|

-

|

|

Increase in other liabilities**.....................................

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in other liabilities**..................................

|

+

|

-

|

|

Increase in capital accounts**.............................

|

-

|

+

|

|

Decrease in capital accounts**..........................

|

+

|

-

|

|

Increase in reserve requirements.................

|

-***

|

||

Decrease in reserve requirements.................

|

+***

|

||

* These factors represent assets and liabilities of the Treasury. Changes in them typically affect reserve balances through a related change in the Federal Reserve Banks' liability "Treasury deposits."

** Included in "Other Federal Reserve accounts" as described on page 35.

*** Effect on excess reserves. Total reserves are unchanged.

Note: To the extent that reserve changes are in the form of vault cash, Federal Reserve accounts are not affected.

Changes in the Amount of Currency Held by the Public

Changes in the amount of currency held by the public typically follow a fairly regular intramonthly pattern. Major changes also occur over holiday periods and during the Christmas shopping season - times when people find it convenient to keep more pocket money on hand. (See chart.) The public acquires currency from banks by cashing checks. When deposits, which are fractional reserve money, are exchanged for currency, which is 100 percent reserve money, the banking system experiences a net reserve drain. Under the assumed 10 percent reserve requirement, a given amount of bank reserves can support deposits ten times as great, but when drawn upon to meet currency demand, the exchange is one to one. A $1 increase in currency uses up $1 of reserves.

Changes in the amount of currency held by the public typically follow a fairly regular intramonthly pattern. Major changes also occur over holiday periods and during the Christmas shopping season - times when people find it convenient to keep more pocket money on hand. (See chart.) The public acquires currency from banks by cashing checks. When deposits, which are fractional reserve money, are exchanged for currency, which is 100 percent reserve money, the banking system experiences a net reserve drain. Under the assumed 10 percent reserve requirement, a given amount of bank reserves can support deposits ten times as great, but when drawn upon to meet currency demand, the exchange is one to one. A $1 increase in currency uses up $1 of reserves.Suppose a bank customer cashed a $100 check to obtain currency needed for a weekend holiday. Bank deposits decline $100 because the customer pays for the currency wi th a check on his or her transaction deposit; and the bank's currency (vault cash reserves) is also reduced $100. See illustration 15.

Now the bank has less currency. It may replenish its vault cash by ordering currency from its Federal Reserve Bank - making payment by authorizing a charge to its reserve account. On the Reserve Bank's books, the charge against the bank's reserve account is offset by an increase in the liability item "Federal Reserve notes." See illustration 16. The reserve Bank shipment to the bank might consist, at least in part, of U.S. coins rather than Federal Reserve notes. All coins, as well as a small amount of paper currency still outstanding but no longer issued, are obligations of the Treasury. To the extent that shipments of cash to banks are in the form of coin, the offsetting entry on the Reserve Bank's books is a decline in its asset item "coin."

The public now has the same volume of money as before, except that more is in the form of currency and less is in the form of transaction deposits. Under a 10 percent reserve requirement, the amount of reserves required against the $100 of deposits was only $10, while a full $100 of reserves have been drained away by the disbursement of $100 in currency. Thus, if the bank had no excess reserves, the $100 withdrawal in currency causes a reserve deficiency of $90. Unless new reserves are provided from some other source, bank assets and deposits will have to be reduced (according to the contraction process described on pages 12 and 13) by an additional $900. At that point, the reserve deficiency caused by the cash withdrawal would be eliminated.

When Currency Returns to Banks, Reserves Rise

After holiday periods, currency returns to the banks. The customer who cashed a check to cover anticipated cash expenditures may later redeposit any currency still held that's beyond normal pocket money needs. Most of it probably will have changed hands, and it will be deposited by operators of motels, gasoline stations, restaurants, and retail stores. This process is exactly the reverse of the currency drain, except that the banks to which currency is returned may not be the same banks that paid it out. But in the aggregate, the banks gain reserves as 100 percent reserve money is converted back into fractional reserve money.

When $100 of currency is returned to the banks, deposits and vault cash are increased. See illustration 17. The banks can keep the currency as vault cash, which also counts as reserves. More likely, the currency will be shipped to the Reserve Banks. The Reserve Banks credit bank reserve accounts and reduce Federal Reserve note liabilities. See illustration 18. Since only $10 must be held against the new $100 in deposits, $90 is excess reserves and can give rise to $900 of additional deposits.

To avoid multiple contraction or expansion of deposit money merely because the public wishes to change the composition of its money holdings, the effects of changes in the public's currency holdings on bank reserves normally are offset by System open market operations.

6The same balance sheet entries apply whether the individual physically cashes a paper check or obtains currency by withdrawing cash through an automatic teller machine.

7Under current reserve accounting regulations, vault cash reserves are used to satisfy reserve requirements in a future maintenance period while reserve balances satisfy requirements in the current period. As a result, the impact on a bank's current reserve position may differ from that shown unless the bank restores its vault cash position in the current period via changes in its reserve balance.

15 When a depositor cashes a check, both deposits and vault cash reserves decline.

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Vault cash reserves . . -100

|

Deposits . . . . -100

|

(Required . . -10)

|

|

(Deficit . . . . 90)

|

16 If the bank replenishes its vault cash, its account at the Reserve Bank is drawn down in exchange for notes issued by the Federal Reserve.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserve accounts: Bank A . . . -100

|

|

F.R. notes . . . +100

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Vault cash . . . . . . . . +100

|

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . -100

|

17 When currency comes back to the banks, both deposits and vault cash reserves rise.

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Vault cash reserves . . +100

|

Deposits . . . . +100

|

(Required . . . +10)

|

|

(Excess . . . . +90)

|

18 If the currency is returned to the Federal reserve, reserve accounts are credited and Federal Reserve notes are taken out of circulation.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserve accounts: Bank A . . +100

|

|

F.R. notes . . . . . -100

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Vault cash . . . . . -100

|

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . . . +100

|

Page 18

Changes in U.S. Treasury Deposits in Federal Reserve Banks

Reserve accounts of depository institutions constitute the bulk of the deposit liabilities of the Federal Reserve System. Other institutions, however, also maintain balances in the Federal Reserve Banks - mainly the U.S. Treasury, foreign central banks, and international financial institutions. In general, when these balances rise, bank reserves fall, and vice versa. This occurs because the funds used by these agencies to build up their deposits in the Reserve Banks ultimately come from deposits in banks. Conversely, recipients of payments from these agencies normally deposit the funds in banks. Through the collection process these banks receive credit to their reserve accounts.

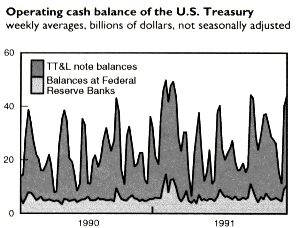

The most important nonbank depositor is the U.S. Treasury. Part of the Treasury's operating cash balance is kept in the Federal Reserve Banks; the rest is held in depository institutions all over the country, in so-called "Treasury tax and loan" (TT&L) note accounts. (See chart.) Disbursements by the Treasury, however, are made against its balances at the Federal Reserve. Thus, transfers from banks to Federal Reserve Banks are made through regularly scheduled "calls" on TT&L balances to assure that sufficient funds are available to cover Treasury checks as they are presented for payment. (8)

The most important nonbank depositor is the U.S. Treasury. Part of the Treasury's operating cash balance is kept in the Federal Reserve Banks; the rest is held in depository institutions all over the country, in so-called "Treasury tax and loan" (TT&L) note accounts. (See chart.) Disbursements by the Treasury, however, are made against its balances at the Federal Reserve. Thus, transfers from banks to Federal Reserve Banks are made through regularly scheduled "calls" on TT&L balances to assure that sufficient funds are available to cover Treasury checks as they are presented for payment. (8)Bank Reserves Decline as the Treasury's Deposits at the Reserve Banks Increase

Calls on TT&L note accounts drain reserves from the banks by the full amount of the transfer as funds move from the TT&L balances (via charges to bank reserve accounts) to Treasury balances at the Reserve Banks. Because reserves are not required against TT&L note accounts, these transfers do not reduce required reserves.(9)

Suppose a Treasury call payable by Bank A amounts to $1,000. The Federal Reserve Banks are authorized to transfer the amount of the Treasury call from Bank A's reserve account at the Federal Reserve to the account of the U.S. Treasury at the Federal Reserve. As a result of the transfer, both reserves and TT&L note balances of the bank are reduced. On the books of the Reserve Bank, bank reserves decline and Treasury deposits rise. See illustration 19. This withdrawal of Treasury funds will cause a reserve deficiency of $1,000 since no reserves are released by the decline in TT&L note accounts at depository inst itutions.

Bank Reserves Rise as the Treasury's Deposits at the Reserve Banks Decline

As the Treasury makes expenditures, checks drawn on its balances in the Reserve Banks are paid to the public, and these funds find their way back to banks in the form of deposits. The banks receive reserve credit equal to the full amount of these deposits although the corresponding increase in their required reserves is only 10 percent of this amount.

Suppose a government employee deposits a $1,000 expense check in Bank A. The bank sends the check to its Federal Reserve Bank for collection. The Reserve Bank then credits Bank A's reserve account and charges the Treasury's account. As a result, the bank gains both reserves and deposits. While there is no change in the assets or total liabilities of the Reserve Banks, the funds drawn away from the Treasury's balances have been shifted to bank reserve accounts. See illustration 20.

One of the objectives of the TT&L note program, which requires depository institutions that want to hold Treasury funds for more than one day to pay interest on them, is to allow the Treasury to hold its balance at the Reserve Banks to the minimum consistent with current payment needs. By maintaining a fairly constant balance, large drains from or additions to bank reserves from wide swings in the Treasury's balance that would require extensive offsetting open market operations can be avoided. Nevertheless, there are still periods when these fluctuations have large reserve effects. In 1991, for example, week-to-week changes in Treasury deposits at the Reserve Banks averaged only $56 million, but ranged from -$4.15 billion to +$8.57 billion.

8When the Treasury's balance at the Federal Reserve rises above expected payment needs, the Treasury may place the excess funds in TT&L note accounts through a "direct investment." The accounting entries are the same, but of opposite signs, as those shown when funds are transferred from TT&L note accounts to Treasury deposits at the Fed.

9Tax payments received by institutions designated as Federal tax depositories initially are credited to reservable demand deposits due to the U.S. government. Because such tax payments typically come from reservable transaction accounts, required reserves are not materially affected on this day. On the next business day, however, when these funds are placed either in a nonreservable note account or remitted to the Federal Reserve for credit to the Treasury's balance at the Fed, required reserves decline.

End page 18.

Page 19.

19 When the Treasury builds up its deposits at the Federal Reserve through "calls" on TT&L note balances, reserve accounts are reduced.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserve accounts: Bank A . . -1,000

|

|

U.S. Treasury deposits . . +1,000

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . . -1,000

|

Treasury tax and loan note account

. . -1,000

|

(Required . . . . 0)

(Deficit . . 1,000)

|

20 Checks written on the Treasury's account at the Federal Reserve Bank are deposited in banks. As these are collected, banks receive credit to their reserve accounts at the Federal Reserve Banks.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserve accounts: Bank A . . +1,000

|

|

U.S. Treasury deposits . . . -1,000

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . . +1,000

|

Private deposits . . +1,000

|

(Required . . . +100)

(Excess . . . . . +900)

|

End of page 19.

Changes in Federal Reserve Float

A large proportion of checks drawn on banks and deposited in other banks is cleared (collected) through the Federal Reserve Banks. Some of these checks are credited immediately to the reserve accounts of the depositing banks and are collected the same day by debiting the reserve accounts of the banks on which the checks are drawn. All checks are credited to the accounts of the depositing banks according to availability schedules related to the time it normally takes the Federal Reserve to collect the checks, but rarely more than two business days after they are received at the Reserve Banks, even though they may not yet have been collected due to processing, transportation, or other delays.

The reserve credit given for checks not yet collected is included in Federal Reserve "float ."(10) On the books of the Federal Reserve Banks, balance sheet float, or statement float as it is sometimes called, is the difference between the asset account "items in process of collection," and the liability account "deferred credit items." Statement float is usually positive since it is more often the case that reserve credit is given before the checks are actually collected than the other way around.

Published data on Federal Reserve float are based on a "reserves-factor" framework rather than a balance sheet accounting framework. As published, Federal Reserve float includes statement float, as defined above, as well as float-related "as-of" adjustments.(11) These adjustments represent corrections for errors that arise in processing transactions related to Federal Reserve priced services. As-of adjustments do not change the balance sheets of either the Federal Reserve Banks or an individual bank. Rather they are corrections to the bank's reserve position, thereby affecting the calculation of whether or not the bank meets its reserve requirements.

An Increase in Federal Reserve Float Increases Bank Reserves

As float rises, total bank reserves rise by the same amount. For example, suppose Bank A receives checks totaling $100 drawn on Banks B, C, and D, all in distant cities. Bank A increases the accounts of its depositors $100, and sends the items to a Federal Reserve Bank for collection. Upon receipt of the checks, the Reserve Bank increases its own asset account "items in process of collection," and increases its liability account "deferred credit items" (checks and other items not yet credited to the sending bank's reserve accounts). As long as these two accounts move together, there is no change in float or in total reserves from this source. See illustration 21.

On the next business day (assuming Banks B, C, and D are one-day deferred availability points), the Reserve Bank pays Bank A. The Reserve Bank's "deferred credit items" account is reduced, and Bank A's reserve account is increased $100. If these items actually take more than one business day to collect so that "items in process of collection" are not reduced that day, the credit to Bank A represents an addition to total bank reserves since the reserve accounts of Banks B, C, and D will not have been commensurately reduced.(12) See illustration 22.

A Decline in Federal Reserve Float Reduces Bank Reserves

Only when the checks are actually collected from Banks B, C, and D does the float involved in the above example disappear - "items in process of collection" of the Reserve Bank decline as the reserve accounts of Banks B, C, and D are reduced. See illustration 23.

On an annual a verage basis, Federal Reserve float declined dramatically from 1979 through 1984, in part reflecting actions taken to implement provisions of the Monetary Control Act that directed the Federal Reserve to reduce and price float. (See chart.) Since 1984, Federal Reserve float has been fairly stable on an annual average basis, but often fluctuates sharply over short periods. From the standpoint of the effect on bank reserves, the significant aspect of float is not that it exists but that its volume changes in a difficult-to-predict way. Float can increase unexpectedly, for example, if weather conditions ground planes transporting checks to paying banks for collection. However, such periods typically are followed by ones where actual collections exceed new items being received for collection. Thus, reserves gained from float expansion usually are quite temporary.

On an annual a verage basis, Federal Reserve float declined dramatically from 1979 through 1984, in part reflecting actions taken to implement provisions of the Monetary Control Act that directed the Federal Reserve to reduce and price float. (See chart.) Since 1984, Federal Reserve float has been fairly stable on an annual average basis, but often fluctuates sharply over short periods. From the standpoint of the effect on bank reserves, the significant aspect of float is not that it exists but that its volume changes in a difficult-to-predict way. Float can increase unexpectedly, for example, if weather conditions ground planes transporting checks to paying banks for collection. However, such periods typically are followed by ones where actual collections exceed new items being received for collection. Thus, reserves gained from float expansion usually are quite temporary.10Federal Reserve float also arises from other funds transfer services provided by the Fed, and automatic clearinghouse transfers.

11As-of adjustments also are used as one means of pricing float, as discussed on page 22, and for nonfloat related corrections, as discussed on page 35.

12If the checks received from Bank A had been erroneously assigned a two-day deferred availability, then neither statement float nor reserves would increase, although both should. Bank A's reserve position and published Federal Reserve float data are corrected for this and similar errors through as-of adjustments.

21 When a bank receives deposits in the form of checks drawn on other banks, it can send them to the Federal Reserve Bank for collection. (Required reserves are not affected immediately because requirements apply to net transaction accounts, i.e., total transaction accounts minus both cash items in process of collection and deposits due from domestic depository institutions.)

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Items in process of collection . . +100

|

Deferred credit items . . +100

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Cash items in process of collection . . +100

|

Deposits . . . . . . . +100

|

22 If the reserve account of the payee bank is credited before the reserve accounts of the paying banks are debited, total reserves increase.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Deferred credit items . . -100

|

|

Reserve account: Bank A . . +100

|

BANK A

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Cash items in process of collection . . -100

|

|

Reserves with F.R. Banks . . . +100

(Required . . . . +10)

(Excess. . . . . . +90)

|

|

23 But upon actual collection of the items, accounts of the paying banks are charged, and total reserves decline.

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Items in process

of collection . . . . . . -100

|

Reserve accounts:

Banks B, C, and D . . . . . -100

|

BANK B, C, and D

|

Assets

|

Liabilities

|

Reserves with F.R.Banks . . -100

|

Deposits . . . . . . -100

|

(Required . . . -10)

(Deficit . . . . . 90)

|

Page 22.

Changes in Service-Related Balances and Adjustments

In order to foster a safe and efficient payments system, the Federal Reserve offers banks a variety of payments services. Prior to passage of the Monetary Control Act in 1980, the Federal Reserve offered its services free, but only to banks that were members of the Federal Reserve System. The Monetary Control Act directed the Federal Reserve to offer its services to all depository institutions, to charge for these services, and to reduce and price Federal Reserve float.(13) Except for float, all services covered by the Act were priced by the end of 1982. Implementation of float pricing essentially was completed in 1983.

The advent of Federal reserve priced services led to several changes that affect the use of funds in banks' reserve accounts. As a result, only part of the total balances in bank reserve accounts is identified as "reserve balances" available to meet reserve requirements. Other balances held in reserve accounts represent "service-related balances and adjustments (to compensate for float)." Service-related balances are "required clearing balances" held by banks that use Federal Reserve services while "adjustments" represent balances held by banks that pay for float with as-of adjustments.

An Increase in Required Clearing Balances Reduces Reserve Balances

Procedures for establishing and maintaining clearing balances were approved by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System in February of 1981. A bank may be required to hold a clearing balance if it has no required reserve balance or if its required reserve balance (held to satisfy reserve requirements) is not large enough to handle its volume of clearings. Typically a bank holds both reserve balances and required clearing balances in the same reserve account. Thus, as required clearing balances are established or increased, the amount of funds in reserve accounts identified as reserve balances declines.

Suppose Bank A wants to use Federal Reserve services but has a reserve balance requirement that is less than its expected operating needs. With its Reserve Bank, it is determined that Bank A must maintain a required clearing balance of $1,000. If Bank A has no excess reserve balance, it will have to obtain funds from some other source. Bank A could sell $1,000 of securities, but this will reduce the amount of total bank reserve balances and deposits. See illustration 24.

Banks are billed each month for the Federal Reserve services they have used with payment collected on a specified day the following month. All required clearing balances held generate "earnings credits" which can be used only to offset charges for Federal Reserve services.(14) Alternatively, banks can pay for services through a direct charge to their reserve accounts. If accrued earnings credits are used to pay for services, then reserve balances are unaffected. On the other hand, if payment for services takes the form of a direct charge to the bank's reserve account, then reserve balances decline. See illustration 25.

Float Pricing As-Of Adjustments Reduce Reserve Balances

In 1983, the Federal Reserve began pricing explicitly for float,(15) specifically "interterritory" check float, i.e., float generated by checks deposited by a bank served by one Reserve Bank but drawn on a bank served by another Reserve Bank. The depositing bank has three options in paying for interterritory check float it generates. It can use its earnings credits, authorize a direct charge to its reserve account, or pay for the float with an as-of adjustment. If either of the first two options is chosen, the accounting entries are the same as paying for other priced services. If the as-of adjustment option is chosen, however, the balance sheets of the Reserve Banks and the bank are not directly affected. In effect what happens is that part of the total balances held in the bank's reserve account is identified as being held to compensate the Federal reserve for float. This part, then, cannot be used to satisfy either reserve requirements or clearing balance requirements. Float pricing as-of adjustments are applied two weeks after the related float is generated. Thus, an individual bank has sufficient time to obtain funds from other sources in order to avoid any reserve deficiencies that might result from float pricing as-of adjustments. If all banks together have no excess reserves, however, the float pricing as-of adjustments lead to a decline in total bank reserve balances.

Week-to-week changes in service-related balances and adjustments can be volatile, primarily reflecting adjustments to compensate for float. (See chart. ) Since these changes are known in advance, any undesired impact on reserve balances can be offset easily through open market operations.